To revive the personal/introductory section of these initial posts – I’m a sophomore planning to double major in English and sociology. I suppose one could say I have extra-literary interests, but actually, everything in my life tends to come back to literature: my intense devotion to my New England home, for instance, tends to amplify my enjoyment of Frost’s poetry, and vice versa. Everything comes back to words for me, I guess. My literary passions, oddly enough, lie in the South, and in examining the ways in which literature reflects upon and works to shape society, social movements, and identity writ large and small … hence, perhaps, my interest in Irish literature and in poetry: how can literature be a part of a nationalist movement for freedom?

Reading about Thomas — quite different from Yeats in that his cultural pride was entirely separate from his cultural passions — I was intrigued by Hardy’s mention of the role Welsh bardic poetry plays in Thomas’s work, either explicitly or subconciously. The bard has always been central to Welsh tradition and society; according to an etymology dictionary, the term “bard” has been a term of great respect in Wales dating back to its appearance in the sixteenth century.The Welsh literary tradition dates back at least to the sixth century, making it one of the oldest literary traditions in Europe, in spite of the recent decline in the population of Welsh speakers.

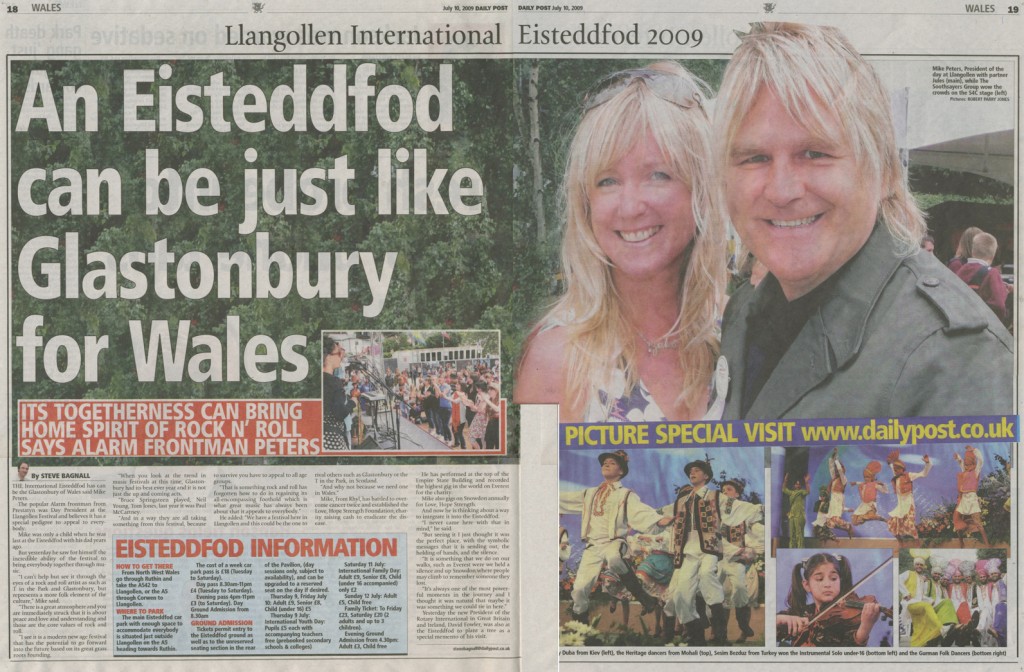

One tradition in particular, which is, as far as I can tell, unique to the Welsh and to Welsh poetry, speaks to the central role of bardic poetry in Wales generally: occurring on national and local levels, the eisteddfod is a yearly festival/competition of poetry and music performances. The term, loosely translated (according to Wikipedia), means “to be sitting together,” implying that such performances are or were once a central organizing structure for Welsh society.

Hardy makes a fairly strong argument that Thomas, along with most Welsh-writers-in-English, was heavily influence by the poetic tradition from which he came, in spite of his denial of it. However, a reading of Thomas alongside Hopkins, another Anglo-Welsh poet (though less readily identifiable as such because he wrote in the nineteenth century), does reveal their close similarities. Hopkins, in spite of writing in primarily English and in primarily Ireland, was clearly influenced by his Welsh roots and by the cynghanedd-esque repetition of sounds. To deny this influence seems like it might limit our reading of Thomas’s poetry, but to ignore his denial seems equally unfair to me.

I can’t help speculating – what must it mean to write in a society that praises poetry so readily, and what must it mean to deny that tradition? Is it even possible to escape? Can one write about a place and a people without also writing about its desires and its foibles?