There’s an ongoing semi-joke between my mom and me that if we go to Scotland, we should visit Hunter Castle (or Hunterston Castle, as a little research turned up its real name to be). This is based mostly on the fact that my grandmother’s maiden name was Hunter, which ultimately means… absolutely nothing, considering there are a lot of Hunters in this world. But the mention of the castle and the clan that I may or may not be distantly connected to piqued my interest.

According to what I know about my ancestry (which isn’t much), the chances of any of my family being royalty is pretty low. All four of my grandparents came from humble roots, and all except for my maternal grandmother were first- or second-generation citizens. (I think.) The only exception to that rule is, again, my maternal grandmother. I refer to her as Gammy and she is my last living grandparent, so I’ll just call her that throughout this post. (My grandfather was called Pap-Pap. I don’t know where these names come from. Apparently it’s what my mother called her grandparents, but I don’t know which and I don’t really know why.)

Gammy’s family is the one that may be sort-of kind-of related to George Washington and sort-of kind-of maybe fought in the Civil War. The most explanation about where that side of the family came from that I’ve gotten, according to my mom, is “Ireland-Scotland-England-ish.” Super descriptive. Anyway, back to the neat Scottish castle.

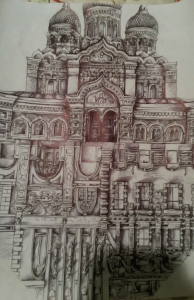

It’s actually not that big or castle-ish.

Hunterston Castle is located in Ayrshire, near to Glasgow, and apparently to one of Glasgow’s important sea access points. (I’ve never been to this place, so I’m going on what I can find, which may or may not be correct. I’m sure Maud will set me straight if I screw up any data.) The castle itself was built in the 13th century by the Laird at the time. There is also a Hunterston House, which is nearby the castle.

If I ever visit, you can bet I’m going to want to say hi to those sheep.

While we’re at it with images and clans, the tartan pattern looks like this.

I’ve seen several different swatches with slightly variant patterns and color intensities, but the green with the blue and red plaid seems to be the common theme. I think there’s some yellow in there, too.

Apparently, the first mention of the Hunter clan in recorded history was in 1116, when a William Hunter was cited as a witness over some sort of land claim dispute pertaining to a Glasgow church. From there, the castle was later built in the 13th century to fortify against Norse invaders. This invader threat was realized in 1263 when the Battle of Largs took place, though how involved any members of the Hunter clan were in that dispute, I can’t confirm or deny. The land itself was granted to a William Hunter (a different William Hunter) by King Robert II in 1374.

Of course, not everybody is as intrigued by dates and history as I am. What’s more interesting on a thought-provoking level is the Hunter clan today. In my research, I came across several websites in various stages of development concerning the modern Hunter clan. The current Chief is a Madam Pauline Hunter of Hunterston, the 30th Laird of the clan and its lands. She appears to spend a fairly significant amount of her time reaching out to the “diaspora” of the clan as a method of preserving and celebrating Scotland’s history, which gives me a nice segway into what this post is actually all about: whether or not I’m even related to this clan, and if I am, does it count?

I’ve mentioned in class a few times that I’m only a wee bit of any sort of Celtic, as it’s about one fourth of my ethnic background… but actually, a whole quarter is kind of a lot when you think about it. A lot of my life has been spent focused on the other aspects of my heritage, though: the half-Jewish part especially, but also the Eastern European roots contributed by my Pap-Pap, whose father was an orphan in the Carpathian Mountains. My mom’s side of the family, the Dulases, still makes pierogi by hand once or twice a year for different special occasions. (We call them pogies, and boy howdy, they do not last long once served. It’s also practically a sin to eat anything else with them except maybe a salad, so get ready for starch.) Regardless, I don’t really know anything about Gammy’s family. I’m sure I could do some serious digging to turn up some results, and apparently there’s a family tree lying around somewhere, but even if I got a look at it, would it tell me anything conclusive?

Many Americans who come from immigrant families seem to know a lot about their family history in comparison to me, and sometimes that makes my own heritage feel a bit… invalidated. I don’t know where my family is from. I know when certain members of my family came to America, but I don’t always know from where, or where their parents might have been from, and so on. All anyone’s been able to give me over time is a shrug because they just don’t know. This might be partially because my family comes from generally modest roots, but that doesn’t seem like it should be the deciding factor. I guess there’s a sense of belonging in having roots in a clan that would be… well, validating for me. But it’s unlikely I really do belong to the clan, regardless of what Gammy’s maiden name was. Hunter isn’t an uncommon last name, and my family does not come from any significant wealth that traces back to Hunterston Estate or the Hunter clan. I might have nothing to do with this family I’ve researched, because a last name is not that much to go on at the end of the day.

I noticed on several of the Hunter-related webpages I visited that they had fairly open sign-up for clan affiliation, so long as you had the right last name, a variation on it, or a relative with that last name. There are events to attend on the grounds during the year. I thought it was strange how open it was, considering pretty much anyone could apply for that whether or not they were really related, but it isn’t my business who Madam Pauline chooses to induct into the family and who she doesn’t.

At some point, I hope I can manage to find out some more about this particular part of my heritage – the Celtic part, that is, however small it may be and however unimportant the people in it may be. Maybe I’m not a member of a fancy clan with its own tartan and a cool, if small, castle. That doesn’t really prove anything except that I’m not a member of the old land-owning gentry class, which I guess is enough to satisfy my socialist heart.

It isn’t going to stop me claiming I’m a vampire because of that great-grandfather from the Carpathian Mountains, though.

(Update: I talked to my mother about that family tree and it turns out I probably am a part of this clan, except the bit of it that emigrated to Ireland and then to America in 1782. So, you know, that’s cool.)

Works Cited:

“Clan Hunter USA.” Clan Hunter USA. 2012. Web. 17 Mar. 2017. <www.clanhunterusa.org/>

“Hunter Clan.” scotlandinoils.com. 2013. Web. 17 Mar. 2017. <www.scotlandinoils.com/clan/Clan-Hunter.html>

Humphrys, Mark. “Hunterston Castle, Ayrshire, Scotland.” HumphrysFamilyTree.com. Web. 17 Mar. 2017. <humphrysfamilytree.com/Hunter/hunterston.html>

“Hunterston History.” Clan Hunter Scotland. Clan Hunter, 2015. Web. 17 Mar. 2017.<clanhunterscotland.com/>.

Fletcher, Craig, and Christopher Jones. “Battle of Largs.” UK Battlefields Resource Centre – Medieval. The Battlefields Trust, 2017. Web. 17 Mar. 2017. <www.battlefieldstrust.com/resource-centre/medieval/battleview.asp?BattleFieldId>.